My research focuses on advancing our knowledge of the turbulent economics of the interwar period through the use of under-studied cases of monetary and financial instability, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe. I am particularly interested in explaining the unusual level of volatility in the economy of the Polish Second Republic (1918-1939), which faced not only a hyperinflation between 1918 and 1924, but also very sharp reversals of flows in the capital account in the later 1920s, and a Great Depression whose severity Romer (1991) identifies as equal to that of the much better-studied Depression in the United States.

My existing work, detailed below, has had two primary focuses. The first has been to bring the Polish literature on the country’s interwar economic experience, the bulk of which was written in the 1960s and 1970s under the constraints of the Iron Curtain and poor access to foreign sources, up to date and into dialogue with the latest comparative debates.

Having done this, I then turned to answering a key question: the Great Depression in Poland was as severe as it was because of the country’s membership of the gold standard, which necessitated, as Knakiewicz (1967) has recognised, a thoroughgoing policy of deflation which constricted monetary, fiscal, and trade policy alike. But why did Poland, a relatively poor, semi-agrarian, net debtor economy, remain on gold almost until the very end, leaving only in April 1936, some three years later than its economic fundamentals would have predicted (Wolf (2008))?

My PhD thesis examines this question in detail and finds that the reasons were at their core political: so long as Poland remained fundamentally dependent on French support in the event of a major war, the Polish government could ill afford to break with the French lead on monetary policy, whatever the economic cost. Conversely, it was France’s declining reliability as a military ally, particularly in the wake of the Rhineland crisis, which was immediately responsible for the Polish decision to change course and impose exchange controls as a prelude to rearmament.

My research plans extend across multiple horizons. Over the next two years, my priority is to complete Money and the Search for Security: Poland and the International Monetary System, 1918-1939 (joint work with William A. Allen). This is a synoptic, book-length history of Polish central banking between the two World Wars which demonstrates how Poland’s monetary policy was subordinated to the country’s perceived geopolitical interests. It is under contract with Cambridge University Press with an expected publication date in 2026.

Once the manuscript is complete, I will also be editing and expanding my PhD chapters into publishable form for submission to journals such as the Economic History Review and European Review of Economic History.

Over the longer term, my main project is likely to be a series of three to six articles which explore the transmission channels through which monetary policy aggravated the Great Depression in Poland. The argument I am interested in making draws on the work on Germany of Borchardt (1991) and Ritschl (1998, 2013) on the role of real-wage rigidity in driving the Great Depression in Poland’s largest neighbour, and extends the discussion of the close parallels in economic structure between Poland and late-Weimar Germany identified in my doctoral dissertation. It proceeds from a general-equilibrium framework: the government’s overriding need to maintain gold reserves at the central bank leads to the adoption of protectionist measures and cartel arrangements which hold wages in industry at an artificially high level (Polish real wages in industry rose some 35% over the course of the Depression) and contributes to mass unemployment in manufacturing. This in turn leads to a spillover of labour into the ‘uncontrolled’ agricultural sector, pushing up agricultural output and (given that grain is generally price-inelastic) driving down prices and revenues. The hypothesis to be tested provides a potential explanation for the so-called “price scissors” between industrial and agricultural products which has been identified by existing scholarship (e.g. Landau and Tomaszewski (1983)) as a cardinal feature of the Depression in Poland, but which has to date remained unaccounted for.

Another question I intend to address is the debate about Poland’s interwar GDP, recently revived by Bukowski, Kowalski and Wroński (2025). They provide annual GDP estimates for 1924-1939 which imply a mean annual growth rate of 2.3%, far above earlier estimates. This is a result which needs to be checked, and there is also an opportunity to refine the measurements to a quarterly or even monthly frequency. I intend to do so by employing the three hundred or so series of ‘headline’ economic variables published monthly by GUS to create a high-frequency index of economic activity, which can be calibrated to GDP, using a method similar to that employed by Mitchell, Solomou, and Weale (2012) for the United Kingdom.

Research Works

Poland and the International Monetary System, 1918-1939 (joint work with William A. Allen, forthcoming with Cambridge University Press)

The history of central banking in Poland between the two World Wars has not received a synoptic treatment, even in Polish. Existing work has either focussed specifically on the second central bank of the period, Bank Polski SA: oftentimes for only a subset of its existence (e.g. Leszczyńska (2013), who limits her account to 1924-1936 and especially 1925-1927). Hardly anything has been written on the war years, when the Bank remained active both in exile and under occupation, and virtually nothing on the bank’s winding-up following the Second World War. Existing studies have likewise neglected the provisional bank of issue of newly independent Poland, the Polska Krajowa Kasa Pożyczkowa, whose archives remain completely untouched by economic historians, as well as the central bank of the Free City of Danzig, which was in a monetary union with Poland throughout its existence. We explore the international dimensions of Polish central banking, including the struggle to balance the country’s monetary interests between French, British, and American interests, and the role of foreign capital in Poland’s stabilisation and recovery from the First World War and hyperinflation. The manuscript is currently approximately 75% complete, and is scheduled for delivery at the end of 2025 with a likely publication date in 2026.

PhD Thesis: ‘We’ll Give Up Our Blood but Not Our Gold’: Money, Debt, and the Balance of Payments in Poland’s Great Depression

Chapter 1: Hyperinflation and Stabilisation in Poland, 1919-1927: ‘War of Attrition’ or Politics by Other Means?

This chapter uses daily-frequency exchange-rate data to investigate the Polish hyperinflation after World War I, a formative episode that accounts for many of the institutions and political choices that shaped Poland’s trajectory during the Great Depression. My main finding is that the Polish hyperinflation was driven by low state capacity and foreign-policy events, not distributional conflict as argued by Alesina and Drazen (1991) and Eichengreen (1995). The timing of the stabilisation clearly substantiates Sargent’s (1981) hypothesis that rational, not adaptive, expectations governed the Polish hyperinflation.

Chapter 2: Sovereign Debt and the Great Depression in Central Europe: Evidence from Transatlantic Bond Markets

I make use of a set of 43,111 sovereign-bond quotations collected at daily frequency for all of the sovereign securities of Poland, Austria, Germany and Hungary listed on the London and New York bond markets between 1927 and 1936 to analyse the propagation of the 1931 crisis throughout Central Europe and shed light on why Poland did not follow Germany off gold, despite having a higher sovereign debt/GDP ratio. I find that, while the Central European debtors suffered a common shock from investor confidence in September 1931, Polish bonds recovered quickly, as Poland’s authoritarian government signalled its willingness to do everything necessary to keep Poland strategically aligned with France in the Gold Bloc.

Chapter 3: Interwar Poland’s Late Exit from Gold: A Case of Government as ‘Conservative Central Banker’

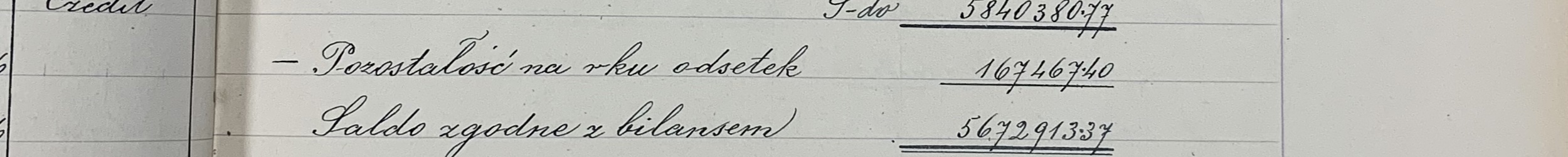

This paper uses high-frequency (thrice-monthly) balance-sheet data from the Bank of Poland, as well as archival evidence from the Bank’s files, to examine in detail why Poland stayed on gold until 1936 and why it was not forced off earlier. My most important finding is that Poland during the Great Depression provides a counterexample to Rogoff’s (1985) argument that delegation of monetary policy to an actor without a social mandate to stabilise output will lead to tighter policy. The evidence shows that, from the 1931 crisis onward, the Bank’s desire to devalue the Zloty was being held in check by the government’s geopolitically motivated determination to maintain convertibility, made effective by a de facto takeover of the Bank by the government. Poland’s exit from gold in 1936 is directly attributable to foreign policy events (Hitler’s Rhineland coup being one), which undermined the value of the French alliance: there is no evidence of the decision being forced by a drop in reserves, as the traditional Polish historiography alleges.

MSc Thesis: Monetary Regime Change and the End of the Great Depression in Poland, 1934-1936

The key contribution of my MSc thesis, written as a prelude to my current PhD work, was to provide a badly needed reinterpretation of the existing historiography on the Great Depression in Poland – most of it written behind the Iron Curtain in the 1960s and 1970s – in the light of modern macroeconomic theory. It is narrative rather than quantitative in focus, but serves as an accessible primer on the course of the Depression in Poland.

Shorter Writing

Brexit Lessons from the ‘Silesian Backstop’ of 1919 – 1925. LSE BREXIT Blog, 15 April 2019.